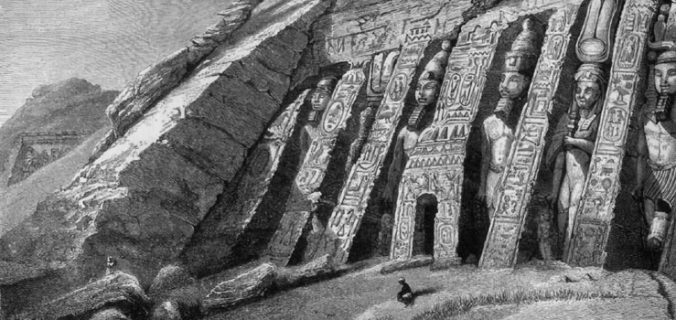

The midday sun was beating down mercilessly, and most of the tourists had already returned to the dahabiyeh for luncheon. The kitchen crew rang the bell twice, and when these requisite courtesies had been paid, they began their meal without the Painter, who hadn’t yet returned from the ruins. He was determined to have Abu Simbel to himself, to paint the colossal statues in full light and explore the grounds without hundreds of fellow English tourists. But he couldn’t help but be drawn closer to the structure, captivated by the hieroglyphs and cartouches half-buried in the sand. He wanted to trace their edges, sketch them into his notebook. A small group of figures looked familiar. He had seen them before, over a doorway or two, he thought. That could mean that just below where he was standing, there could be a door into the temple, hidden and undisturbed for hundreds–maybe thousands–of years. He began to dig, huge handfuls of sand cascading down to fill the space of every handful he threw aside.

Back on the boat, the tourists were finishing their lunch when a messenger arrived with a penciled note. One of tourists, perhaps the lady novelist, read the note aloud, “Pray come immediately–I have found the entrance to a tomb. Please send some sandwiches.”

***

Amelia Edwards was one of those rare Victorian prodigies who began writing almost from the time she could talk, and published her first poems and short stories around the age of 12. At 24, when most women of the era were giving birth to their third or fourth child, Edwards published her first novel, My Brother’s Wife, the life story of a young, studious man who falls unhappily in love with, as the novel suggests, his brother’s wife.

Amelia Edwards was one of those rare Victorian prodigies who began writing almost from the time she could talk, and published her first poems and short stories around the age of 12. At 24, when most women of the era were giving birth to their third or fourth child, Edwards published her first novel, My Brother’s Wife, the life story of a young, studious man who falls unhappily in love with, as the novel suggests, his brother’s wife.

I first came to know Edwards through her 1873 travel book, Untrodden Peaks and Unfrequented Valleys: A Midsummer Ramble in the Dolomites. Her title is an homage to the memoirs of earlier female travel writers, like Mary Shelley’s Rambles in Germany and Italy. The same year that Edwards publishes her Italian travels, she set sail on a journey, as her title has it, A Thousand Miles up the Nile. Edwards is clearly a novelist at heart, and her representation of her travelling companions is reminiscent of Little Dorrit’s fellow travellers, whom Dickens identifies as “the Chief” and “the insinuating traveller.” Similarly, Edwards has “the Idle Gentleman,” and “the Painter,”–who has just discovered the tomb at Aboo Simbel [sic]–and Edwards herself is identified as “the Writer.” The only person who does not appear as a trope character is “L,” a poorly disguised double for Edwards’s partner, Ellen Braysher.

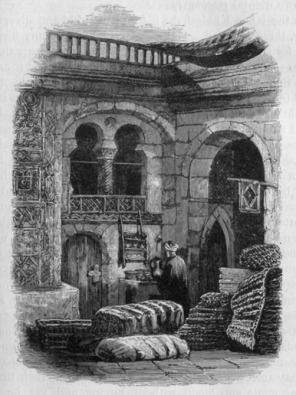

When the note arrives summoning the travellers to the tomb, they abandoned their lunch and within ten minutes were frantically digging: “Heedless of possible sunstroke, unconscious of fatigue, we toiled on our hands and knees, as for bare life, under the burning sun.” (481). When the opening was just large enough to squeeze through, the group entered, one at a time, standing atop of a sandrift that filled the room. By the light of a single candle, Edwards and her companions could see “the painted frieze running around just under the ceiling; the bas-relief sculptures on the walls, gorgeous with unfaded colour.” Over the next few days, the tourists hired more and more locals, from around 40 to up to 100, to remove sand from the inner chamber until the room began to take shape.

As the troupe was clearing sand and probing walls for hidden doors and apertures, “All at once the Idle Man thrust his fingers into a skull!” He continued digging in the sand in near darkness until he found a clay bowl filled with caked sand, then, suddenly, another, much smaller skull. And within a few minutes, they located the complete skeletons: “The remains were those of a child and small grown person–probably a woman. The teeth were sound; the bones wonderfully delicate and brittle. As for the little skull (which had fallen apart at the sutures), it was pure and fragile in texture as the cup of a water-lily” (491). The party of tourists continued digging, carefully sifting through the sand, hoping to find “mummies, perhaps, and sarcophagi, and funereal gods, and jewels, and payri, and wonders without end!”

They didn’t. Disappointed, they returned to the boat and continued their journey up the Nile.

But something inside Amelia Edwards was changed. She became obsessed with Egyptology. She became an advocate for archaeology, particularly in parts of Egypt that were rarely visited by tourists. In 1882, she co-founded, along with Reginald Stuart Poole of the British Museum’s Department of Coins and Medals, the Egypt Excavation Fund. Edwards attracted support and contributions from notable friends like Robert Browning, which were poured into archaeological digs in Egypt.

Edwards became a recognizable figure in a field dominated by men, while the Egypt Excavation Fund bankrolled some of the most important finds in history. Unlike many of the treasure hunters of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Fund was particularly concerned with preserving artifacts and documenting antiquities. Most expositions included skilled young artists eager for adventure and opportunity, among them, a talented seventeen year-old named named Howard Carter. After WWI, the Egypt Excavation Fund became the Egypt Exploration Society, as the organization is known today. The society continues to support Egyptological scholarship and publishes the Journal of Egyptian Archaeology.

With proceeds from her books and popular lecture tours, Edwards continued to support the Fund financially for the remainder of her life. When she died in 1892, she bequeathed her library and £2,400 to University College London to endow the Edwards Professorship in Egyptian Archaeology and Philology. She stipulated that her friend, the legendary (and notoriously racist) Sir William Matthew Flanders Petrie should be named the inaugural Edwards Professor. Petrie is best known for pioneering the scientific method, including advanced dating techniques, as well as emphasizing the importance of everyday objects, rather than only studying only pharaohs and gods. Many of the objects Petrie uncovered and meticulously studied are now at UCL’s Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology.

Edwards is buried in Bristol, England, next to her partner Ellen and Ellen’s daughter Sarah. Edwards’s importance in LGBTQ+ history was officially recognized in fall 2016, when her grave was listed as a Grade II landmark. Befittingly, her tombstone is an obelisk and, instead of a coverstone there is a stone ankh, the Egyptian symbol of life.