As the rage for phantasmagoria crossed the Channel, one of the most popular performers was a Parisian, Paul de Philipsthal (known variously as Phylidor, Paul Philidor, and Paul Filadort). De Philipsthal was a very early pioneer in phantasmagoria, staging his first performances in 1792, several years before Robertson’s and may have served as inspiration. Robertson raised the medium to an art form through technological innovation and soon surpassed Philipsthal in fame. Faced with heavy competition and political uncertainty, de Philipsthal went to London, where he gave regular performances of “Optical Illusions and Mechanical Pieces of Art,” according to the playbill of the opulent Lyceum Theatre. In 1803, he offered to share the stage with another refugee from Napoleon’s Paris, a skilled wax sculptor named Marie Tussaud.

The Lyceum shows were an enormous success, and, together, they toured Ireland, Scotland, and England, performing for thousands, including other pioneers of optics, Sir Thomas Young, who later introduced the wave theory of light, and Sir David Brewster, a brilliant optician and inventor. Brewster later penned Letters on Natural Magic, Addressed to Sir Walter Scott, which details how phantasmagoria and other devices and tricks work and how they had been misused. He describes how kings, despots, and priests had historically used simple acoustic (like the Oracle at Delphi) and optical illusions (including mirrors, magnifying glasses, various lenses, etc.) to claim divine power over their subjects: “When the tyrants of antiquity were unable or unwilling to found their sovereignty on the affections and interests of their people, they sought to entrench themselves in the strongholds of supernatural influence, and to rule with the delegated authority of heaven” (2). By Brewster’s time, however, these effects were used less to hold power over uneducated subjects than to entertain the masses.

Wherever phantasmagoric performances appeared, audiences were entertained, and although many of the effects were well known, people continued to be terrified, shrieking, fainting, and batting at ghosts with sticks. Historian and literary critic Terry Castle asks what we’re all thinking: “How realistic were the ‘ghosts’? Strange as it now seems, most contemporary observers stressed the convincing nature of the phantasmagoric apparitions and their power to surprise the unwary… One should not underestimate, by any means, the powerful effect of magic lantern illusions on eyes untrained by photography and cinematography” (39).

In the twenty-first century, we (especially scholars and historians) have a tendency to smirk at the naïveté of audiences, readers, and spectators of the eighteenth, nineteenth, and, increasingly, twentieth centuries. Future generations will likely smirk at us. What draws Castle to these histories is a curiosity similar to my own. She sees the history of phantasmagoria as “the history of imagination” itself (29). The concept of being haunted, both visually and psychologically, is inextricable from modern consciousness and popular culture. Robertson may not have invented ghosts, but his influence is undeniable.

Over a decade before his articles in Household Words, Dickens wrote The Christmas Carol, about the wealthy capitalist Ebenezer Scrooge, who is haunted by the ghosts of Christmases Past, Present, and Future. A reviewer in The Spectator, published December 23rd, 1844, wrote that “the ludicrous and the terrible, the real and the visionary, are curiously jumbled together, as in the phantasmagoria of a magic lantern” (The Annotated Christmas Carol, v.). Dickens specifically describes the ghosts as transparent because that’s how Robertson’s ghosts appeared.

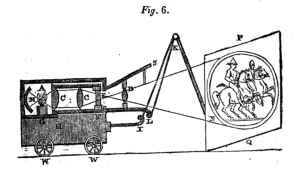

Dickens followed the popularity of A Christmas Carol with a sequel, The Haunted Man and the Ghost’s Bargain, and an 1862 stage version of The Haunted Man used actual phantasmagoria, including a new innovation by Henry Dircks that could project a live actor onto glass on stage, giving the effect that a dynamic ghost—not a static slide—was delivering lines and performing with the actor. The Dircksian Phantasmagoria, as it was then (only briefly) called, was staged by a scientist of the Royal Polytechnic Institution named John Henry Pepper, whose ghosts are still used in stage productions around the world.

Long after the performances fell out of fashion, the metaphor of phantasmagoria remained in circulation. From the literature of Dickens, Edgar Allen Poe, and W. B. Yeats, phantasmagoria made its way from our imagination into our zeitgeist, describing a very particular anxiety—being haunted by the past, afraid of the future, and feeling out of place within one’s own time. Castle explains, “[I]n everyday conversation, we affirm that our brains are filled with ghostly shapes and images, that we ‘see’ figures and scenes in our minds, that we are ‘haunted’ by our thoughts, that our thoughts can, as it were, materialize before us, like phantoms, in moments of hallucination, waking dreams, or reverie.”

Although the technology of the fantoscope was surpassed by later cinematic advancements, the phantasmagoria was a precursor to a visual aesthetic of horror as entertainment. Whenever we go to the cinema for a horror film, there’s a little bit of Robertson’s legacy lurking in the shadows. We had always been afraid of the dark, but Robertson made us afraid of light—of translucent ghosts and glowing spectres.

A decade after his phantasmagoric performances, Robertson joined forces with his old mentor, Jacques Charles, and became one of the first people to ascend in a hydrogen balloon, all the while conducting experiments in barometric pressure, boiling point, and evaporation, at increasingly higher altitudes. In 1803, he set a new altitude record using the hot-air powered Montgolfier model. He would go on to travel by balloon throughout Europe, where he was sometimes greeted as a hero, and in Russia, where he was suspected of being a spy. But no one could doubt that he was–as he had been with the fantoscope–a master of spectacle.

Robertson died in 1837 and was buried in Père Lachaise Cemetary, alongside other French luminaries. One side of his tomb bears a bas relief of a crowd looking up in wonder at a hot air balloon overhead. Children climb higher to see; a woman looks through binoculars, a man through a spyglasses. The other side shows the same grouping of people, but this time, they gasp in horror at encroaching demons, ghosts, and skeletons. Here, children hide their faces, one woman covers her eyes with her hands. Some in the crowd look away; others can’t. Even in death, Robertson showed us different ways of looking.