Every year I recommit myself to a resolution to use this blog as a sort of intellectual diary, documenting my research projects, thoughts from events and lectures, and book reviews. But since I haven’t done that, here’s a quick survey of my favorite reads from the year, in the order that I read them.

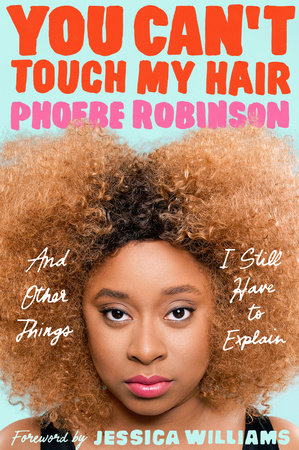

Funniest Read

Best Memoir/ True-Crime

I’ve been friends with Alexandria Marzano-Lesnevich for several years now, so I was lucky enough to read excerpts of The Fact of a Body long before Vogue called it a “true crime masterpiece…of profound revelation” and dozens of reviewers, from Audible.com to The Sunday Times, compared its author to Truman Capote. The book is half true-crime drama, unfolding the case surrounding convicted pedophile and murderer Ricky Langley, and half personal memoir of Marzano-Lesnevich’s own childhood abuse and emerging queerness. It’s not a mystery in the traditional true-crime sense–we know who did it from the beginning–but, rather, it’s a story (or two stories) about how we craft narrative and make meaning. In a book ostensibly about physical evidence and corporeality, both narratives embody the resistance to easy definition.

Best Academic Book

In the interest of full disclosure, I must state that the author was the chair of my dissertation committee, but with my dissertation far behind me, I hope this review seems less sycophantic. Jennifer Green-Lewis’s new book Victorian Photography, Literature and the Invention of Modern Memory: Already the Past is one of the most stunningly beautiful works of scholarship I’ve ever read. How often can you truly say that? Here’s one of my favorite excerpts, on the history of the camera obscura: “Eighteenth-century drawing-room walls, fifteenth-century sheets of paper, tenth-century scrims of fabric, the cool stone interiors of grottos and caves—all functioned as sites of spectatorship, spaces of varying sizes throughout human history into which light pictures of the outside were invited but could not be made to stay. And there were also natural spaces where there were no human beings at all but where prismatic images nonetheless danced, as presumably they still dance, on the dark insides of hollow trees or abandoned buildings or rock crevices.”

In the interest of full disclosure, I must state that the author was the chair of my dissertation committee, but with my dissertation far behind me, I hope this review seems less sycophantic. Jennifer Green-Lewis’s new book Victorian Photography, Literature and the Invention of Modern Memory: Already the Past is one of the most stunningly beautiful works of scholarship I’ve ever read. How often can you truly say that? Here’s one of my favorite excerpts, on the history of the camera obscura: “Eighteenth-century drawing-room walls, fifteenth-century sheets of paper, tenth-century scrims of fabric, the cool stone interiors of grottos and caves—all functioned as sites of spectatorship, spaces of varying sizes throughout human history into which light pictures of the outside were invited but could not be made to stay. And there were also natural spaces where there were no human beings at all but where prismatic images nonetheless danced, as presumably they still dance, on the dark insides of hollow trees or abandoned buildings or rock crevices.”

Reading the book brought back memories of countless lectures and conversations about places where our respective research interests overlap–a preoccupation with visual culture and its relationship to literature, a fascination with the history of photographic technologies and their cultural implications. What surprised me most was that my own research has evolved and expanded into new territories that were never discussed or hinted at, and yet those same threads are followed in this book, but much more skillfully that I could have done. It is just the sort of book I would write, if I could write such a book.

I’ll leave you with this last quote that I’ve thought about and parroted a thousand times since reading it: “To claim that Dickens, or any other Victorian novelist, is ‘photographic,’ or ‘cinematic,’ is to miss the more interesting (and logical) possibility that film is actually Dickensian.”

Best Novel

To be honest, I don’t read very many novels. Even in grad school, most of my research was on non-fiction: travel writing, guidebooks, and art criticism. Of course, I have a deep, abiding love for the great Victorian novel, but I haven’t picked up a triple-decker since I defended my dissertation. So this may be a controversial choice for “best novel,” but Ann Patchett’s State of Wonder kept me awake into the early hours of the morning. For a novel that’s largely about waiting and the passage of time (though to a less degree than Patchett’s Bel Canto), the book is still surprisingly suspenseful. It has frequently been compared to Heart of Darkness, and with good reason (it also shares some of its more problematic colonialist undertones), but what makes the novel enjoyable is Patchett’s prose. She describes everything with such vivid detail that I’m not altogether sure that she hasn’t navigated Brazilian waterways, been shot with poisonous arrows, or slaughtered a giant snake with her bare hands.

Best Essay Collection

Teju Cole is perhaps best known for his breakout 2011 novel Open City, but he’s also an art historian, avid photographer, and prolific essayist. Known and Strange Things is a masterful collection of works that previously appeared in The New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker, The Atlantic, and elsewhere. His topics range from the travel writing of James Baldwin, Cole’s near-obsession with W. G. Sebald, the Australian composer Peter Sculthorpe, Nigerian politics, American politics, Derek Walcott, and the photographs of Saul Leiter and others.

Teju Cole is perhaps best known for his breakout 2011 novel Open City, but he’s also an art historian, avid photographer, and prolific essayist. Known and Strange Things is a masterful collection of works that previously appeared in The New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker, The Atlantic, and elsewhere. His topics range from the travel writing of James Baldwin, Cole’s near-obsession with W. G. Sebald, the Australian composer Peter Sculthorpe, Nigerian politics, American politics, Derek Walcott, and the photographs of Saul Leiter and others.

I was drawn to Cole because we share many of the same heroes–Susan Sontag, Roland Barthes, John Berger. Even when he’s not specifically writing about them, they’re still there, haunting his prose in ways that Cole is probably hyper-aware, as when he compares the colonial gaze of white photographers to images taken by Malian photographer Sedou Keïta: “In the former, the women are being looked at against their will, captive to a controlling gaze. In the latter, they look at themselves as in a mirror, an activity that always involves seriousness, levity, and an element of wonder.” It’s clearly an homage to Berger, and I find it comforting that Cole can write so gracefully, free from the spectral anxiety of influence. I can only hope that someday someone will read an essay of mine and say, “Ah, she’s clearly influenced by Cole.”

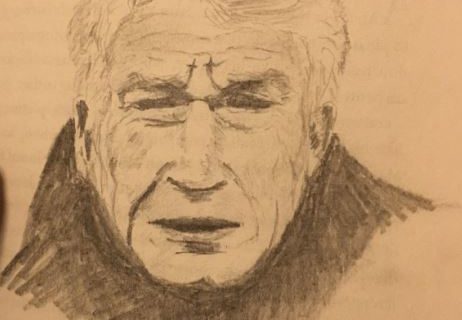

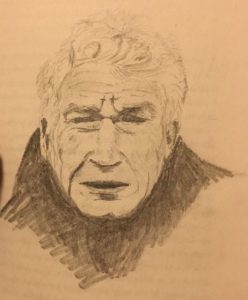

Favorite Sketch

Okay, so this isn’t a book, but it’s in a book….now. I was reading Known and Strange Things in a coffeeshop one day, and it was suddenly too noisy to read, but I was thinking a lot about John Berger, who passed away January 2, 2017. Berger was a gifted artist–you can see a short clip of Berger sketching Tilda Swinton from the documentary The Seasons in Quincy: Four Portraits of John Berger. I was thinking about that when I started this sketch in the blank space after Cole’s chapter about him.

Okay, so this isn’t a book, but it’s in a book….now. I was reading Known and Strange Things in a coffeeshop one day, and it was suddenly too noisy to read, but I was thinking a lot about John Berger, who passed away January 2, 2017. Berger was a gifted artist–you can see a short clip of Berger sketching Tilda Swinton from the documentary The Seasons in Quincy: Four Portraits of John Berger. I was thinking about that when I started this sketch in the blank space after Cole’s chapter about him.