Looking for the Picturesque: Sightseeing, Visual Culture, and the Literature of Tourism in the Long Nineteenth Century

A Digital Dissertation Companion

This ongoing project shows the intersections between my dissertation and innovative digital humanities tools and methodologies. Rather than submitting a completely digital dissertation project, this digital companion includes information that simply cannot be described by the traditional text-based dissertation format. While this companion will not be addressed during my dissertation defense, it will be open to methods of peer-review currently available and developing within the global Digital Humanities community.

This page will soon include a full abstract, chapter synopses, resources, bibliographies, and micro-projects for each chapter. A brief description of in-progress projects can be found below each chapter tab.

As part of this digital companion, I have built a Trailer (not yet compatable with smart-devices) to highlight the dissertation chapters, the visual culture discussed in my research, and the interactive nature of this born-digital project.

Table of Contents

Introduction

This introduction provides much of the historical and theoretical context for my research, beginning in the late eighteenth century with the Grand Tour. At the time, tourists often used a Claude glass, a darkened, convex mirror whose reflection was said to possess the aesthetic qualities of a painting by French Romantic landscape painter Claude Lorrain. In order to use the Claude glass, the tourist must turn his--I say his because the Grand Tourist was almost certainly male--back on the site to gaze into the mirror, often painting the reflection, rather than the landscape. One of the principle arguments of my dissertation is that literature, whether guidebooks, travelogues, or novels, acts as a textual Claude glass, a lens that frames and aesthetically mediates the site/sight/sign.

The use of the Claude glass was popularized by William Gilpin, whose Three Essays on the Picturesque defines the rules of picturesque sight-seeing. According to Gilpin's model, the picturesque is tripartite, consisting of a foreground, often ornamented by happy, rustic peasants; the far-distance, usually hazy mountains or cloud formations; and, finally, the middle-distance, where the eye of the viewer was drawn, often to crumbling ruins or cliff-perched castles. While many scholars believe the pictureque had disappeared by the early 1810s, my project traces the picturesque throughout the nineteenth century and into the twentieth. The legacy of the picturesque persists in sight-seeing practices which artificially and aesthetically distances the tourist from the sight, while seeing local populations as simple, happy ornaments.

If tourists are, as Jonathan Culler has argued, "unsung armies of semioticians...fanning out in search of the signs of Frenchness, typical Italian behavior," etc., I argue that picturesque aesthetics are the basis of those sign-systems. In other words, my project examines aesthetics and semiotics as cocentric touristic practices.

The Dissertation Timeline

This Dissertation Timeline provides a concise chronology of major movements in travel literature and tourism from the Napoleonic War until the First World War. It is built using an open-source Javascript app called TimelineJS, developed by Northwest University's Knight Lab.

Chapter 1. "What Ought to Be Seen": Murray, Baedeker, Ruskin, and the Guidebook Industry

This chapter examines the history of the guidebook from early prototypes, such as John Chetwode Euastace's 1802 A Classical Tour through Italy, which Dickens lampooned in Little Dorrit, to the restricted travel of the First World War and the demise of Murray's Handbooks for Travellers in 1915.

A complete abstract is coming soon.

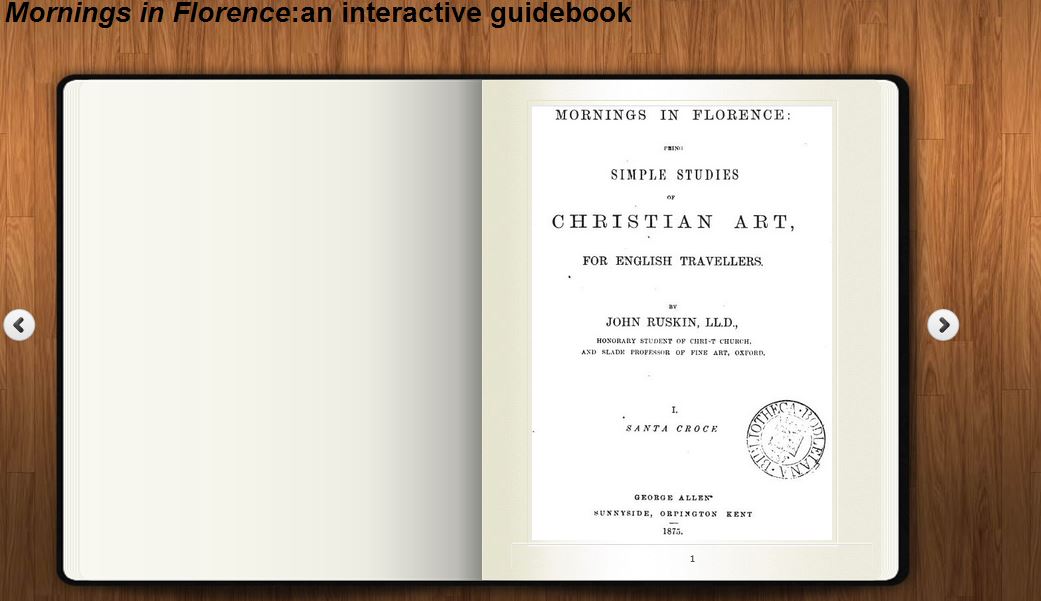

John Ruskin's Mornings in Florence: An Interactive Guidebook

When Ruskin began writing Mornings in Florence, he wrote in his diary, "Lay long awake planning my attack on Murray." Ruskin was irritated at what he called the "tourist hurry" encouraged by Murray's Handbook for Travellers, and took great delight in pointing out its flaws and inaccuracies. A large portion of Ruskin's criticism was class-based: Murray's was the guidebook of choice (and for decades the only guidebook, as we know the term today) for the uneducated masses brought to Europe by Thomas Cook and others. Ruskin wanted to produce a guidebook for the cultured upper-middle-class traveller, like himself. The result is that much of his own book is a commentary as much about Murray as it is about Florence. In the years following Mornings in Florence'a publication, E. M. Forster had as much to say about Ruskin as Ruskin had about Murray.

Ruskin's short chapters were meant to be "in the places which they describe, or before the pictures to which they refer," but most of his readers today are scholars or armchair travellers, neither of which may have the extensive knowledge of Florentine art to know every fresco or tomb which Ruskin describes. This interactive edition of Ruskin allows these readers, for the first time, to see the sights he describes. I have also cross-referenced original passages from Murray and Forster.

Thusfar, "Morning One" is the only chapter available, with the remaining chapters following soon. You can read more about the planning and building of this project on my blog.

Chapter 2. 'Everyone has wept and Gurgled': Originality, Subjectivity, and the Hypertextuality of Travel Writing in the Long Nineteenth Century

The second chapter of my dissertation discusses the travel writings and memoirs of a diverse group of British and American writers, includin Charles Dickens, Amelia Edwards, Elizabeth Robbins Pennell, Henry James, Vernon Lee, Edith Wharton, and Lilian Bell.

A full synopsis of this chapter is coming soon.

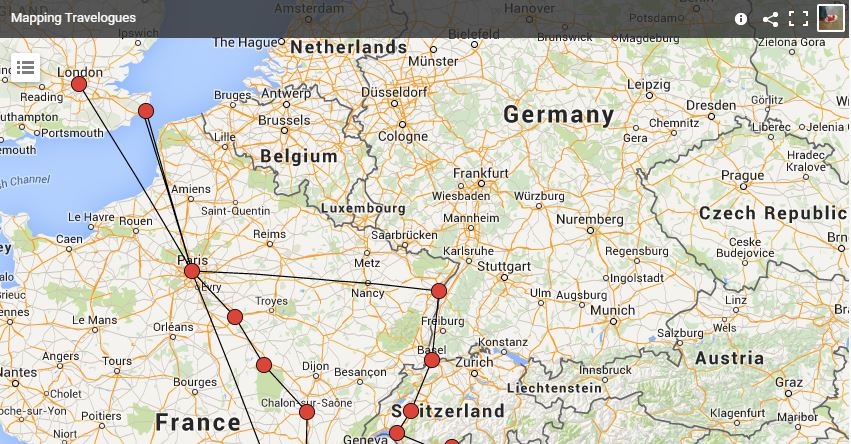

The micro-project for this chapter uses GIS technology to map itineraries from multiple travelogues. These itineraries are presented in layers, allowing two or more itineraries to be compared for spatial and diachronic analysis. Users will be able to see instances where writers follow similar routes, sometimes visiting the same cities at the same times. The map will also show the changing shape of the Grand Tour, as British and American tourism becomes increasingly global. In the first phase of this project, only travelogues and memoirs discussed in my dissertation will be mapped. In future phases, this project will be open-access for crowd-sourced itineraries, building an extensive library of data on travel literature.

A user-friendly interface is still being developed, and will be published here as soon as it is available.

Mapping Travel Writing

The first stage of this beta project maps the locations mentioned in Charles Dickens's travelogue Pictures from Italy. More texts and features will be added as the project progresses.

Chapter 3. Beyond 'The Surface of Things': Tourism and the Deconstruction of the Picturesque in Victorian and Edwardian Fiction

This chapter examines fictional tourists and their travels, from Charles Dickens's Little Dorrit to E.M. Forster's A Room with a View. Tourists are usually shown as stereotypcal guidebook readers, blindly following their text abd blissfully ignorant of "authentic" culture. This chapter seeks to complicate these tourists types, showing a much more nuanced representation of tourism as a narrative device.

The project that accompanies this chapter is still in the early planning stages, but will include TEI analysis and topic modelling. As a preview of what's to come, the image to the left is a Word Cloud made with Wordle, modeling the third chapter of the dissertation.

The Picturesque vs. the Photographic

In the opening pages of E. M. Forster's "The Story of Panic" (1902), a group of English tourists picnic on an Italian hillside, admiring the view. One tourist exlaims, "What a pretty picture it would make!" Another adds, "Many a famous European gallery would be proud to have a landscape a tithe as beautiful as this upon its walls." As they all join in praise of the "landscape," "vista," and "panorama," one voice counters the others. Leyland, a snobby, artistic young man, argues, "On the contrary...it would make a very poor picture. Indeed, it is not paintable at all...Look, in the first place...how intolerably straight against the sky is the line of the hill. It would need breaking up and diversifying. And where we are standing the whole thing is out of perspective. Besides, all the colouring is monotonous and crude...You all confuse the artistic view of Nature with the photographic."

Unlike his companions, Leyland is clearly familiar with William Gilpin's formulae for the picturesque--that the picturesque is never smooth, but requires roughness, variation, and a tripartite perspective consisting of a foreground, middle distance, and far distance. Leyland, and by extention, Forster, would have been among the few tourists in Italy who still understood the picturesque in terms of eighteenth century aesthetics. Most people, like the tourists upon the hillside, understood "picturesque" to simply mean "beautiful," as we usually use the term today.

Most scholars of the nineteenth century have argued that picturesque, as Gilpin and Leyland understand it, had disappeared by the early 1800s, even Jane Austen poked fun at Gilpins rules for being old fashioned. By the 1840s, photography had captured the visual imagination, the last nail in Gilpin's aesthetic coffin.

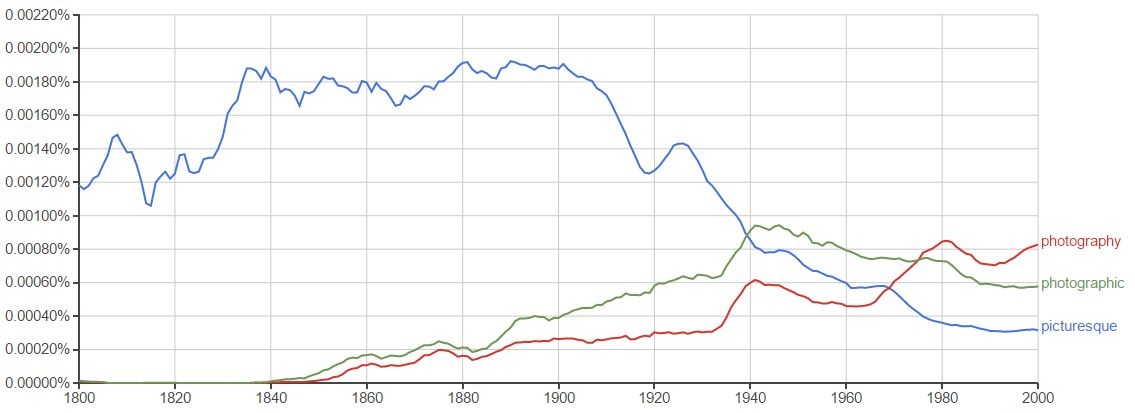

My research seems to show the opposite: that, in fact, the picturesque continues to be central to tourism throughout the nineteenth century and into the twentieth century. The picturesque informed how Forster, Henry James, Vernon Lee, and others saw and understood the landscapes and people around them. Now, with big data applications, such as Google Ngram, we can show exactly how long-lasting discussions of picturesqueare in our publication history. Photography, on the other hand, or even photographic takes much longer to supercede the influence of the picturesque than anyone previous expected.

This Ngram view of picturesque shows that the term was certainly in sharp decline during Austen's time, but not long before 1820, that is, approximately concurrent with the publication of Northanger Abbey, the picturesque was again on the rise. The 1830s saw a marked increase in publications that mention the picturesque; not surprisingly, most of these texts are travel guides, art texts, or a combination of both, such as Heath's Picturesque Annual. By the mid-nineteenth century, books on picturesque scenes, such as J, M. W. Turner's Picturesque Views of the Southern Coast of England (1826), have virtually disappeared, replaced in popularity by Black's Picturesque Tour guidebooks. The picturesque actually begins to disappear from the publication data around the turn of the twentieth century when, as mentioned in the previous chapter, Henry James stops using the term, and Forster openly criticizes its misuse. It is not until around 1939, just prior to the Second World War, that photography or photographic becomes more frequently used in publications than picturesque.

The above paragraph is taken from the dissertation.

Chapter 4. Tourism in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction: Aesthetics and Semiotics in the Ephemera of Travel

This site is under construction. A full description of this chapter is coming soon, accompanied by a currated digital gallery of tourist ephemera.

Coda. After Tourism: A Case Study and a Theory

The dissertation closes with a Coda divided into three sections discussing what happens after tourism. The first section is a short case study on the souvenirs, ephemera, and scrap books of American art collector Isabella Stewart Gardner. The second section presents a theory of "Post-Tourism." Tourism is often discussed as a chronological step which marked the end of "travel." If that case holds, there must be something that comes next, a post-post-modern method of seeing and experiencing the world. The third and final section of the Coda presents a few conclusions, both in terms of "wrapping things up," as well as my own ultimate findings as this dissertation draws to an end.

This chapter will have several micro projects related to both the themes of Coda and meta-projects on the dissertation itself.