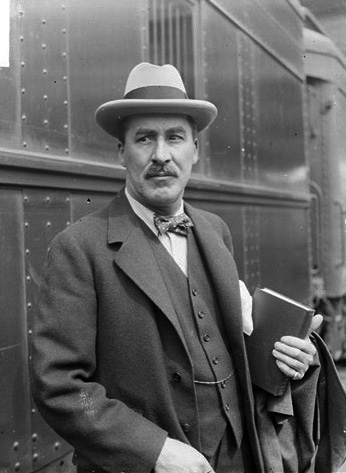

Howard Carter went to Egypt in 1902 at the age of 17. Though his family was not particularly wealthy, they had connections and secured Carter a job as an artist with the Egypt Exploration Fund, an organization co-founded by the famed travel writer and Egyptologist Amelia Edwards.

Among his belongings, Carter packed art supplies, books, and a small chisel, a birthday gift from his grandmother. After a few years of hard work and gaining an impressive grasp of Egyptian history and culture, both ancient and contemporary, Carter began leading excavations with modest success and, it must be said, a few public and humiliating missteps. While still a teenager, Carter discovered and excavated the tombs of Thutmose II and Thutmose III. By the time he found the tombs, however, they had already been plundered hundreds, if not thousands, of years before.

Among his belongings, Carter packed art supplies, books, and a small chisel, a birthday gift from his grandmother. After a few years of hard work and gaining an impressive grasp of Egyptian history and culture, both ancient and contemporary, Carter began leading excavations with modest success and, it must be said, a few public and humiliating missteps. While still a teenager, Carter discovered and excavated the tombs of Thutmose II and Thutmose III. By the time he found the tombs, however, they had already been plundered hundreds, if not thousands, of years before.

Carter had been in Egypt for only five years when he was introduced to Lord Carnarvon, a wealthy English aristocrat who was born and raised at Highclere Castle, though his ancestral home is better known in popular imagination as Downton Abbey (The downstairs scenes are filmed on a London set, because the lower levels of Highclere house Egyptian artifacts). Carnarvon hired Carter to lead his expedition in part because he appreciated Carter’s interdisciplinary approach, which melded art and science with a deep respect for Egyptian culture. Rather than digging haphazardly and destructively, as many archaeologists did, Carter drew grids on a map, quartered them into smaller triangles, and methodically moved–or, rather, had his workers move–dirt and rubble from one grid to another, working through triangle by triangle. The grid method was practiced extensively in art but, at the time, wasn’t used in digs. This would prove to be the missing piece to solving the mystery of the Valley of the Kings. But they would have to wait.

Carter had been in Egypt for only five years when he was introduced to Lord Carnarvon, a wealthy English aristocrat who was born and raised at Highclere Castle, though his ancestral home is better known in popular imagination as Downton Abbey (The downstairs scenes are filmed on a London set, because the lower levels of Highclere house Egyptian artifacts). Carnarvon hired Carter to lead his expedition in part because he appreciated Carter’s interdisciplinary approach, which melded art and science with a deep respect for Egyptian culture. Rather than digging haphazardly and destructively, as many archaeologists did, Carter drew grids on a map, quartered them into smaller triangles, and methodically moved–or, rather, had his workers move–dirt and rubble from one grid to another, working through triangle by triangle. The grid method was practiced extensively in art but, at the time, wasn’t used in digs. This would prove to be the missing piece to solving the mystery of the Valley of the Kings. But they would have to wait.

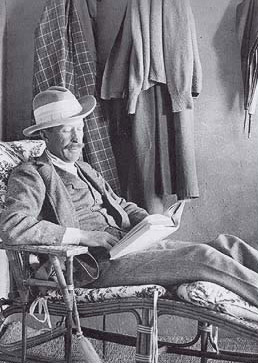

Permits were required to excavate in Egypt, and for years, the only permit to dig in The Valley of the Kings was held by Theodor Davis and Edward Ayrton. Time after time, Davis and Ayrton thought they had found Tut’s tomb, but they always came up empty handed. They successfully found several major sites, but they were disappointed that the tomb of the then-little-known king Tutankhamen always alluded them. It was only after they ran out resources, enthusiasm, and, they thought, places to look, that the men finally relinquished the permit. In his 1912 book The Tombs of Harmhabi and Touatankhamanou, Davis declared the valley to be “exhausted.”

Carter was still convinced, and somehow managed to keep Carnarvon convinced, that the tomb of the boy king was still out there, hidden somewhere in the rubble of a hundred digs. With Davis out of the picture, Carter was able to obtain the permit to dig in the Valley of the Kings, and dig he did, and he kept digging for seven years, working alongside his close collaborators Arthur Mace and Arthur Callendar and a team of hundreds of Egyptian men and young boys whose backs were broken and whose names are lost to history. They found objects here and there, but no signs of a tomb, as square after square of Carter’s grid was crossed out. All the while, they ignored the skeptics and voices in their head insisting that Davis and Ayrton had already cleaned the Valley dry, down to the bedrock.

Carter was still convinced, and somehow managed to keep Carnarvon convinced, that the tomb of the boy king was still out there, hidden somewhere in the rubble of a hundred digs. With Davis out of the picture, Carter was able to obtain the permit to dig in the Valley of the Kings, and dig he did, and he kept digging for seven years, working alongside his close collaborators Arthur Mace and Arthur Callendar and a team of hundreds of Egyptian men and young boys whose backs were broken and whose names are lost to history. They found objects here and there, but no signs of a tomb, as square after square of Carter’s grid was crossed out. All the while, they ignored the skeptics and voices in their head insisting that Davis and Ayrton had already cleaned the Valley dry, down to the bedrock.

Then the war happened.

From 1914 – 1917, Carter remained in Egypt, working as a translator for the British government, probably dreaming of the day he could leave the bureaucratic office for good and get back into the sand. Finally, victory was declared, Germany was defeated, Carter reassembled his team, and Carnarvon continued bankrolling the project. But by 1922, Carnarvon had run out of enthusiasm too, and with the post-war economy still lagging, he was increasingly worried about the financial strain. He gave Carter one more season.

Carter was worried, but he could feel that he was close. On November 1, 1922, Carter commenced his last season of excavation, starting where the previous year’s dig had left off, excavating not around the other archaeological sites, as Davis had done, but under the ancient ruins of huts built to house the workers that built the tomb of Ramses II. After five more days, Carter found it–the entrance to a tomb covered in plaster and royal seals. Worried that someone would open the tomb before he had the chance, he and his men covered the entrance with rubble, and Carter telegraphed Lord Carnarvon in England. And then he waited.

Carter also wired Arthur Callendar, whom he trusted would help in the excavation, and procured donkeys, camels, and other supplies needed to begin removing rubble and fully open the tomb. Finally, nearly three weeks later, on November 24, 1922, Lord Carnarvon arrived inEgypt. The rubble around the entrance was cleared, and they noticed the first distressing signs that they were perhaps not the first to discover the tomb. The plaster wall covering the entrance of the tomb had large patches that were a difficult color and clearly a different age. The tomb had likely been disturbed, as so many others, robbed and resealed.

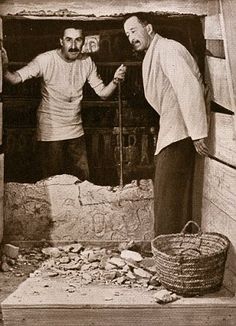

Under the close supervision of the Chief Inspector of the Antiquities Department, a measure required by law, Carter and his men opened the first doorway, breaking through the seals covered with the cartouche of Tutankhamen. Behind the door was a passage, filled from ground to ceiling with rubble and rubbish, making it clear that someone didn’t want this tomb to be disturbed. As reassuring as that fact was, the rubbish filling the passage included pottery, stonework, jar seals, and shards of funerary objects from other pharaohs before and after Tutankhamen’s. Carter began to believe that this was not a tomb at all, but a royal cache, a hiding place for treasure that had been used for centuries, opened and resealed time and time again. If this was true, they could find a storehouse of treasures or an empty pit; either way, they wouldn’t find the tomb. Finally, they reached the end of the long, descending passage and found another doorway.

Under the close supervision of the Chief Inspector of the Antiquities Department, a measure required by law, Carter and his men opened the first doorway, breaking through the seals covered with the cartouche of Tutankhamen. Behind the door was a passage, filled from ground to ceiling with rubble and rubbish, making it clear that someone didn’t want this tomb to be disturbed. As reassuring as that fact was, the rubbish filling the passage included pottery, stonework, jar seals, and shards of funerary objects from other pharaohs before and after Tutankhamen’s. Carter began to believe that this was not a tomb at all, but a royal cache, a hiding place for treasure that had been used for centuries, opened and resealed time and time again. If this was true, they could find a storehouse of treasures or an empty pit; either way, they wouldn’t find the tomb. Finally, they reached the end of the long, descending passage and found another doorway.

Like the first doorway, the second also showed signs of broken seals and patchy plaster work. Someone had been here before, and there was no way to know if the doors lead to empty rooms except to keep pressing on, half expecting to find another passageway filled with rubbish. By this time, Carter was joined in the passage by Lord Carnarvon and his 21 year-old daughter, Lady Evelyn, a woman who had joined the obsessive quest for most of her life.

Using the chisel his grandmother had given him for his 17th birthday, Carter, now a man of 48, made a small hole in the upper left corner of the sealed door. He wrote in his journal, “Candles were procured–the all important tell-tale for foul gases when opening an ancient subterranean excavation.” The candle flickered as hot air, trapped in the tomb for thousands of years, rushed out. Something was behind the doorway. Maybe it was the tomb that had consumed Carter’s days and nights and years. Maybe it was only an empty room.

Carter widened the hole, just enough room to allow his eye and the faint light from the candle dance around the room. Behind him, Carnarvon and Lady Evelyn grew impatient. “Can you see anything?” Carnarvon asked.

“Yes,” Carter replied. “Wonderful things.”