In popular culture, when we imagine archaeology, we inevitably think of Indiana Jones. Sexy, glamorous, and hyper-masculine–Indiana Jones is archaeology’s Platonic ideal. Steven Spielberg and George Lucas famously modeled the character on James Bond, but instead of ink-pen bombs, umbrella guns, and such gadgets, Indiana Jones used something even more powerful–his expansive knowledge of mythology, ancient history, and dead languages. It’s not surprising that the franchise inspired millions of bookish kids to pay attention in history class.

If I wanted an Indiana Jones costume–and yes, females can dress as Indiana Jones, too–I could go out for the whole kit: khakis, boots, leather jacket, satchel, whip, and of course, the fedora. In fact, all you really need to recognize Indiana Jones as Indiana Jones is the hat. That one sign enacts and entire mythology around the character and evokes a geography of mysterious ruins from the Mayan pyramids to Petra. We see the fedora, and, instantly, we can’t get John Williams’s theme out of our heads because, I have to admit, aesthetics are not entirely visual.

I’ve always assumed that the stereotype must be frustrating to actual archaeologists, but apparently that’s not the case. Marilyn Johnson writes in Lives in Ruins: Archaeology and the Seductive Lure of Human Rubble, “Every archaeologist I interviewed worked Indiana Jones into the conversation, usually with affection, as if mentioning a daredevil older brother….Archaeology department costume parties double as Indiana Jones Conventions. ‘For whatever reason,’ one female grad student confided, ‘the guys all own fedoras and whips'” (129). It’s not an altogether bad problem to have. Jones was also a history professor, but that profession never enjoys the same cultural cache. Maybe they should throw more costume parties. But I guess archaeologists deserve something for all their hard work, since they rarely reap their reward in adventure, fortune, and glory. So let them have the cool hat.

While some signs are easy to recognize and read, other elements of aesthetic languages aren’t so easily translated. We might feel that something captures our imagination, but can’t say precisely what it is–there’s just something about the look or feel of a movie or photograph that makes us want to enter into that world.

For Indiana Jones, it might be the films’ neo-noir tone. Aesthetically, the Indiana Jones films look like a hybrid of Maltese Falcon and Boris Karloff-esque horror, with a little comic-book DNA thrown in for fun. It’s clearly pulling from a range of influences, from 1930s serials to 1950s action films, to frame-by-frame recreations of Scrooge McDuck comic books. My own favorite Ur-Indy is a tossup between Humphrey Bogart in The Treasure of Sierra Madre and Charleston Heston in The Secret of the Incas (1954), in which Heston’s character searches for gold at Machu Picchu, romances the beautiful woman on the run, steals airplanes, and delivers sardonic one-liners. Oh, yes, and he wears this:

But there’s something else too, something that can’t quite be defined, something you can’t put your finger on, and at least a part of that has to do with how we imagine time. One of the films’ strengths is its periodization. Spielberg and Lucas could have set the films in the 1980s, but instead they chose the 1930s–the heyday of archaeology. On a practical level, the films are far less dated than they would have been had if set in 1981, but it’s also part of the films’ imaginative pull. Aesthetics often depend upon a fantasy of time travel. But, of course, Indiana Jones isn’t really set in the 1930s, it’s set in an imaginary, hyper-aestheticized 1930s, something we could describe as spatio-temporal aesthetics or, to draw on Bakhatin, chronotopic aesthetics. These aesthetics have permeated culture so deeply that we can’t even imagine archaeology or Egyptology, for that matter, without seeing through the mist of Indiana Jones.

But there’s something else too, something that can’t quite be defined, something you can’t put your finger on, and at least a part of that has to do with how we imagine time. One of the films’ strengths is its periodization. Spielberg and Lucas could have set the films in the 1980s, but instead they chose the 1930s–the heyday of archaeology. On a practical level, the films are far less dated than they would have been had if set in 1981, but it’s also part of the films’ imaginative pull. Aesthetics often depend upon a fantasy of time travel. But, of course, Indiana Jones isn’t really set in the 1930s, it’s set in an imaginary, hyper-aestheticized 1930s, something we could describe as spatio-temporal aesthetics or, to draw on Bakhatin, chronotopic aesthetics. These aesthetics have permeated culture so deeply that we can’t even imagine archaeology or Egyptology, for that matter, without seeing through the mist of Indiana Jones.

***

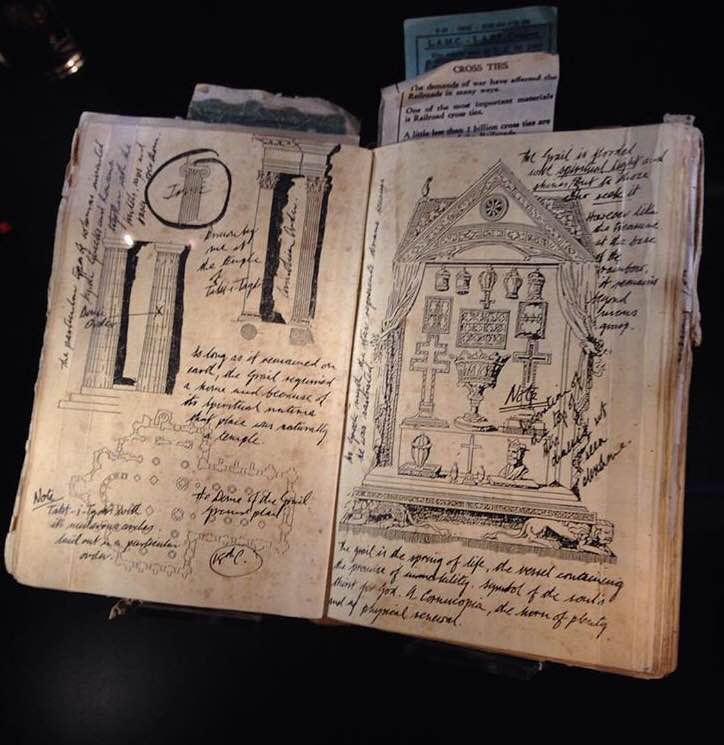

Last summer, the National Geographic Museum here in Washington, DC opened an exhibit called Indiana Jones and the Adventure of Archaeology. It featured an array of artifacts from all of the world–some of which I will discuss more in future posts–along with a lot of costumes, props, and art from the films. Fans of The Last Crusade will recognize the photo to the right as Henry Jones, Sr.’s Grail Notebook, and the picture below (taken by Flickr user Mary Harrsch) is concept art for the Venetian library scene. You can find more photos from the exhibit here.

Last summer, the National Geographic Museum here in Washington, DC opened an exhibit called Indiana Jones and the Adventure of Archaeology. It featured an array of artifacts from all of the world–some of which I will discuss more in future posts–along with a lot of costumes, props, and art from the films. Fans of The Last Crusade will recognize the photo to the right as Henry Jones, Sr.’s Grail Notebook, and the picture below (taken by Flickr user Mary Harrsch) is concept art for the Venetian library scene. You can find more photos from the exhibit here.

Until next time, you can fantasize about researching in this painting.

Spielberg and Lucas have never publicly acknowledged the debt that they owe to the movie SECRET OF THE INCAS when they created Indiana Jones. Only the costume designer from RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK, Deborah Nadoolman, mentions the Heston film as the major influence. Spielberg and Lucas claim it was the 1930’s serials, plus Bogart in THE TREASURE OF THE SIERRA MADRE, that inspired them to develop Indiana Jones.