The Klieg lights swept over the gathering crowd and cut through the dark October sky for the first premier in movie history. Limousines lined the street as far as the eye could see down Hollywood Boulevard. One by one, chauffeurs–the bibs and buttons of their paramilitary uniforms gleaming from the open-top cabs–eased up to the courtyard entranced, climbed down from the car, and opened the back door.

The men always emerged first, wearing tuxedos and top hats. With white scarves draped over their shoulders, they extended a hand to the passenger still waiting in the backseat. At first, all you could see was a satin glove as the women slowly maneuvered their wide hats and fur-trimmed gowns out of the car. The crowd was too ecstatic, jumping and screaming, to hear the emcee announcing the arrival of screen legends like Charlie Chaplin and Mary Pickford.

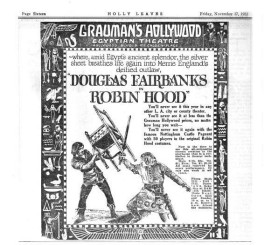

Each celebrity beamed towards the press, heard the thunder of a thousand popping cameras, followed by the quick rain of used bulbs shattering as they hit the ground. Swift hands screwed in replacement bulbs, as matinee idols made their way down the red carpet for the world premier of Douglas Fairbanks in Robin Hood,October 18, 1922. It may have been Fairbanks’s movie–he was its star and producer, and even had stock in the theater–but it was Sid Grauman’s show, and its centerpiece was the brand new Grauman’s Egyptian Theatre.

Sid Grauman had chased fame and fortune all over North America, so it’s no wonder he ended up in Los Angeles. While still a young man, Sid and his father left Indiana for the Klondike Gold Rush. Though they never struck it rich in the mines, they earned a little money entertaining prospectors. A few years later, they made their way to San Francisco where they managed vaudeville theaters, as well as showing silent films. They tried everything they could to make the business a success, from expanding theaters along the East Coast–which didn’t catch on–to operating in a tent after the devastating 1906 San Francisco earthquake, which earned the Graumans a commendation from the mayor for keeping the city’s spirits up.

In 1917, the Graumans decided to leave San Francisco and try their luck in Los Angeles. Their first foray into the grand movie palaces of Hollywood was the elaborate Million Dollar Theater, a name popularized by the press because of its exorbitant construction cost. The theater occupied the lower levels of a multi-story, multi-purpose Edison Building that towered over adjacent structures. During the early decades of the twentieth century, California architects still favored Spanish styles to reflect the state’s colonial history. The theater’s facade is covered in exquisitely detailed stonework, a quasi-Spanish Baroque style known as Churrigueresque. The interior featured massive, gold-leafed murals of mythological scenes, though they have since been hidden under layers of paint or above the tin drop ceiling installed during renovations in the 40s and 50s.

With the success of the Million Dollar Theater, the Graumans started making plans for their most elaborate theater yet, but Sid’s father, David, died before construction was complete. They had originally intended the new theater to have a similar Spanish colonial design, which accounts for the building’s terra cotta tilework. Many historians, including Gregory Paul Williams, author of The Story of Hollywood: An Illustrated History, have claimed that Sid Grauman quickly added Egyptian motifs after Howard Carter discovered King Tut’s tomb and Egyptomania spread across the United States. However, the theater actually opened several weeks before Carter’s discovery. In fact, Egyptian revival architecture had been popular in the US for decades, most notably in Masonic temples, and was repopularized in the 1910s by discoveries in the Valley of the Kings. It’s far more likely that Grauman simply wanted to do something different with his new theater, and, drawing his inspiration from Rudolph Valentino’s The Sheik and other blockbuster adventure films of the time, decided to build something completely new.

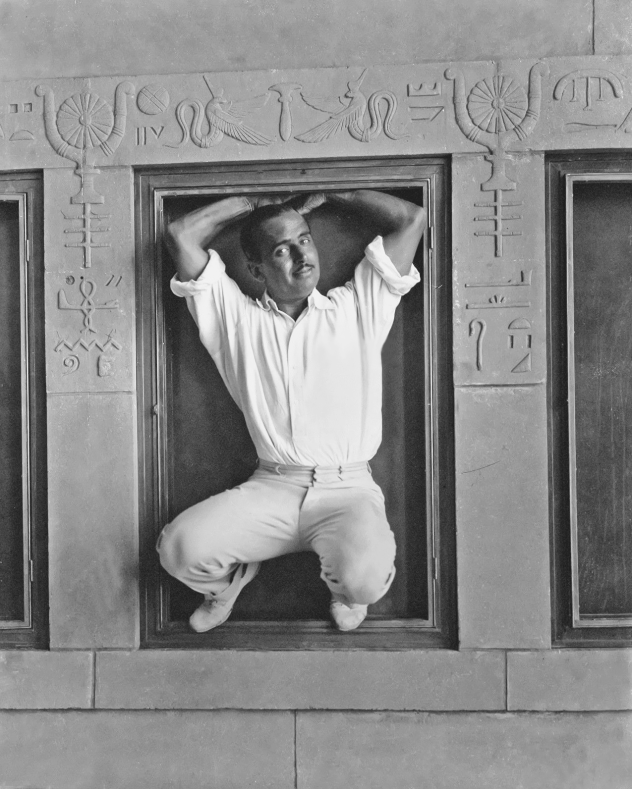

In those days, going to one of the big movie palaces combined both a feature film and a theatrical production. Williams describes: “Female ushers dressed like Cleopatra. Egyptian sentries walked the parapet and called the faithful to matinees” (118). Instead of trailers for coming attractions or the cartoon shorts and newsreels we associate with early cinema, the show began with elaborate prologues, followed by an intermission, before the film was screened. Robin Hood opened with an orchestra playing Aida, followed by a performance on the theater’s enormous organ, then a stage show of Richard the Lionheart that featured dozens of singers and dancers–among them the yet undiscovered dancer-turned-actress Myrna Loy.

Robin Hood ran for a staggering six months, and according to Jeffrey Vance’s book Douglas Fairbanks, the film was so popular that “Hollywood streetcar conductors stopped announcing their Hollywood Boulevard stop with the usual cross street of ‘McCadden Place’ and began shouting ‘All out for Robin Hood’” (148).

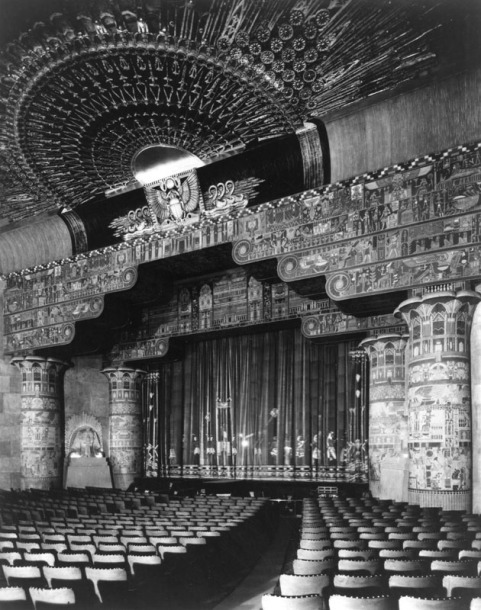

But the show began even earlier as film fans entered the theater through Egyptian columns, guided by the funerary figures painted along the courtyard walls. Inside, the stage was framed by four reed-shaped columns covered in colorful hieroglyphs. A winged scarab, Egyptian symbol of rebirth, hovered across the proscenium, crowned by a massive golden sunburst, signifying Ra. According to LA Times writer Edwin Shallert’s review of opening night: “The sphinxes that adorn the proscenium imply that silence is the tribute of appreciation for the visual drama. The Egyptian inscriptions perhaps suggest that mystic incantation of light which gives life to the shadowed surface of the silver screen” (26 Cooper, Hall, Wannamaker). Many of these interior details were removed to make way for wider-format films, and still others were destroyed in the devastating 1994 earthquake. Very few photographs survive of the intact decor.

The building was designed by Mendel Meyer & Philip Holler, who had recently completed Culver Studios and were in the process of building Cafe Montmartre and the Hollywood Athletic Clubsimultaneously. They would go on to design the First National Bank of Hollywood and the Aztec Theater in San Antonio, TX. When Grauman sold the Egyptian and announced plans for a theater that looked like a Chinese village, he contracted Meyer & Holler again. The firm assigned a young architect named Raymond M. Kennedy. The new theater opened in 1926, and immediately became the most famous movie theater In history.

Despite leaving an indelible mark on Los Angeles’s landscape, the firm declared bankruptcy less than six years after completing the Chinese Theater. Tragedy struck again in 1936 when Mendel Meyer’s brother Gabriel was struck by a car driven by Howard Hughes. Hughes was booked for negligent homicide after a doctor said he had been drinking, and an eyewitness stated that Hughes had been driving fast and erratically before hitting Meyer. Hughes denied the charges, the hospital certified that he was sober, and the eyewitness retracted his story. Hughes was released without charges, but the scandal was unavoidable. Very little is known about Meyer or Holler in the years that followed, though Kennedy went on to have a successful architectural career in L.A.

Grauman died in 1950, but the Egyptian continued operating for several decades until 1994 when the 6.7-magnitude Northridge earthquake severely damaged the building, destroying much of the interior. It stood empty for several years before it was acquired and renovated by American Cinematheque, an LA-based non-profit that preserves film history. It still plays classic films, documentaries, and occasional premiers, when, once again, the Klieg lights circle above, just as they did ninety-five years ago.